Warmer water and smaller run sizes can increase the rates at which salmon spawn away from their home streams, according to a study led by a University of Alaska Fairbanks researcher.

Peter Westley, assistant professor of fisheries at UAF’s School of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences, and a research team analyzed 17 years worth of migration data for 19 populations of hatchery-produced chinook salmon in the Columbia River. The data showed that climate variables influence straying rates, according to findings published online by the Ecological Society of America.

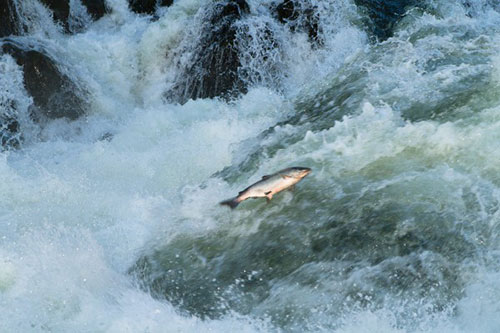

An adult chinook salmon fights its way home upstream.

Photo by Jonathan Armstrong

“Salmon coming back to their home streams after they have spent years at sea feeding is one of those great natural wonders of the world,” Westley said. “We know not all salmon come back to their home stream. A small proportion of them stray to other streams to spawn instead of coming home.”

Columbia River hatcheries release millions of juvenile fish implanted with 1 mm coded wire tags each year. This study used tagging and recapture data from over 150,000 fish tags recovered from 164 unique locations. It would not have been possible without a massive behind-the-scenes effort by people who collected the tags.

“This is among the first papers to look at how climate is shaping rates of straying,” Westley said. “Boiling this down, in terms of what came out of the analyses, when the temperature was higher in the Columbia or in their spawning grounds, they strayed to different watersheds at higher rates.”

In addition to the effect of water temperature, researchers also found a connection between the number of returning fish and the stray rate. Westley explained there is a long-standing assumption in fish ecology work that when many individuals compete in a certain area, some will seek out an area with less competition. His team’s research revealed the opposite; when fewer individual fish returned, the stray rates were higher than when more fish returned together.

The researchers hypothesize that fish may be pooling together to utilize “collective navigation,” so individual fish that don’t detect the necessary cues can still make it home if traveling with a large enough group.

“That really points to an extra concern about when populations get small,” Westley said. “As a population gets smaller, they might actually be straying at higher rates as well, so it could be an extra consequence of populations declining to really small sizes.”

Westley also warned that although temperature and numbers of individuals in the group were strong effects overall, these results should not be extrapolated to make specific predictions for a whole species.

“You can talk about these effects on a broad scale, but when you look at an individual population, they don’t all show the same response,” said Westley. “We saw enough variability that it cautions against assuming that all populations respond the same way.”

The research team for the paper, “Signals of climate, conspecific density, and watershed features in patterns of homing an dispersal by Pacific salmon,” also included Andrew H. Dittman and Eric J. Ward of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Northwest Fisheries Science Center in Seattle, and Thomas P. Quinn of the University of Washington School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences.

http://www.sitnews.us/0415News/041715/041715_salmon_spawning.html