Chinook salmon at the Oregon Hatchery Research Center.

Photo: Emily M. Putman

Young salmon with no experience of the world, and without any guidance, are able to use the Earth’s magnetic field to find locations on the other side of the ocean. Using an inherited magnetic GPS, these fish can find favorable feeding grounds that generations of salmon have frequented.

Chinook salmon hatch in freshwater but migrate to the ocean, where they spend several years. They then make a single return migration to spawn in freshwater, typically near where they hatched, and die after the breeding season.

Nathan Putman, along with colleagues from Oregon State University, the University of Washington, the University of North Carolina, and the Oregon Hatchery Research Center, thought young salmon might be depending on a navigation system based on inherited instructions. Such a map has thus far been demonstrated in only one animal:hatchling loggerhead sea turtles, who use an inherited magnetic map to navigate the open ocean and find feeding grounds.

Salmon, like sea turtles, are able to leave their hatching site and find specific areas in the ocean with no prior experience or elder animals to lead them. An inherited map would let these animals know where they are and be available even with no migratory experience.

Animal Magnetism

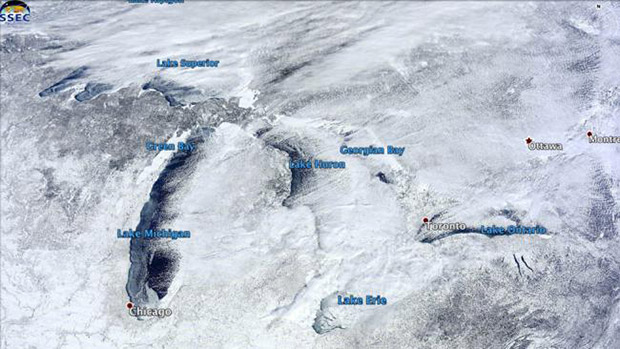

There is a growing body of work showing diverse animals use the magnetic field of the Earth to orient their movements. Because of its gradual and regular gradients across the globe, it seems like one of the few environmental features that would really be useful to an animal traveling long distances.

Putman and his colleagues used a magnetic coil system to test young Chinook salmon with no migratory experience. They created magnetic fields like the ones that exist in parts of the salmon’s ocean range by changing the amperage running through copper wires surrounding the buckets that held the fish. “If the fish used the magnetic field to know where they are, we could make them think that they were north or south of their typical oceanic range by changing the field around them,says Putman.

The team used two magnetic parameters. Field intensity is the magnitude of Earth’s magnetic field, and generally increases as one gets closer to the poles. Inclination angle is the direction of the field relative to Earth’s surface. It is 90° at the poles and progressively less steep at the equator. The gradients of these two parameters are not parallel and so geographic locations have unique magnetic addresses defined by a combination of intensity and inclination. An animal that detects both of these magnetic features would in effect have both latitudinal and longitudinal information about where it was.